Latin America Mining Risk Part V: Reputational Risk

Mining carries immense historical baggage in Latin America that continues to be exploited for political and economic gain by a wide host of actors, ranging from political opposition leaders and crooked local mayors to illicit miners and ambitious NGOs. Therefore, defending one’s reputation is a full-time task that begins from the moment interest is first shown in a Latin American mining property. Reputationally speaking, miners in Latin America are guilty before being proven innocent.

Today, industrial miners bring remarkable technology and safety protocols to their exploration and mining operations. However, blunders still happen, such as the Sanmarco dam burst, as well as recent leaks in Anglo American and Norsk Hydro operations in Brazil. Contaminated glaciers in Chile tarnished the reputation of Barrick Gold in that country. Industrial accidents are common in Latin America, but when they originate from miners, they are even more poorly perceived.

Poorly managed operational risks can quickly snowball into a reputational calamity. In its Copiapó mine in Chile, Compañía Minera San Esteban Primera failed to proactively reveal their safety protocol shortcomings. By contrast, the more experienced Codelco stepped in to rectify the situation and pulled off a stunning rescue of 33 miners trapped deep underground. By calling for national and international help and expertly navigating media, Codelco emerged as a hero in a difficult situation.

But neither acts of god nor sloppy operations are the source of most miner reputational burden. Instead, most reputational attacks come from mining opponents, who are better equipped and more unchecked than ever to wage reputational battle against mining interests.

Reputational Risk Is a Local Affair

In today’s weak mineral price environment and challenging fiscal deficits, most national governments happily roll out the red carpet to attract new mining investment. Since mineral prices began falling in 2013, several national governments have shifted—both via elections and economic necessity—from antagonistic to welcoming. We have seen this shift in Argentina, Ecuador, French Guiana, Brazil, Chile, Dominican Republic and even Venezuela. Certainly, if mineral prices keep rising, then public pressure may oblige these and other governments to switch gears and demand more from miners. However, for the moment, miner reputational risk is predominantly a local problem.

Miners traditionally relied upon national governments, their preferred host country partners, to keep the peace locally, which they did through a combination of transferred royalty payments and coercive actions that were designed to temper local opposition. Scandals happened but were often smothered by national governments who could influence media. Those days are gone. Today, 200 million Latin Americans own smartphones that come with cameras and the ability to upload any video to social media, quickly casting an ugly spotlight on government-sanctioned malfeasance or heavy-handed policing. In this age of digital democracy, national governments across Latin America are under attack as the old ways of doing things, ripe with corruption, are unveiled. Presidential approval levels in Latin America are some of the lowest in the world as voters come to terms with the breadth of poor governance they endure. As a result, presidential power has never been weaker nor more tainted than it is today. Miners are wise not to hitch their reputation wagon to national governments.

National governments lack the infrastructure to govern effectively in many of the remote areas where minerals are found. With their reputations in tatters, they are unwilling to resort to blunt tactics to exercise control. Their absence creates a power vacuum that’s being filled by an assortment of local players, making it even harder for miners to manage their reputations.

Mining Opponents

A very checkered history of mining in most of Latin America has taught local communities to be wary of mining’s impact on their land, water, and way of life. Reputational risk management in Latin America begins by winning the hearts and minds of locals and disproving many of the myths that fester in the minds of locals, based in part on historical precedent but also misinformation, often spread by mining opponents. Regardless of what CSR programs are devised, the process should begin with a thorough surveying of the fears and aspirations of the local community. Without direct contact with the community, miners rely on intermediaries, who bring their own agendas to the table. Ultimately, it is the local community, a body of voters, whose opinions matter most in terms of reputation management.

In the battle to win over the local community and the national public, miners face a variety of opponents, including:

- Local politicians and community leaders: They feel it is their right to receive personal benefit for supporting the mine and are often the ones orchestrating opposition tactics. In the vicinity of almost every mine in Latin America, there is a crooked local leader trying to extort benefit for himself.

- NGOs: These are both well-intentioned and otherwise, and their ambitions sometimes lead them to provoke local conflict in spite of little evidence of miner wrongdoing. Today, some NGOs are active in training local communities on how to oppose mines in Colombia, Argentina, and Guatemala, among other countries.

- Workers unions: They are employed directly by the mine or its subcontractors. Union leaders may be working for paymasters who oppose the mine, such as political opposition groups or organized crime. Poor relationships with unions and their impact on miners’ reputation became a serious issue in Mexico over the last six years as the PRI lost influence of some unions to organized crime.

- Illegal miners: Their business is disrupted by industrial miners and can purchase local and even national political muscle to oppose a mine. In Colombia and Suriname, among others, illegal miners have actively helped repel the incursion of industrial mining to “their” claims. In Venezuela, heavily armed gangs help control illegal miner access to gold in the under-governed Bolívar state near the Brazilian border. The federal government has repeatedly tried to take control of the area using military incursions in the hopes of creating a secure mining environment. Reportedly, hundreds have died in firefights. Any miner investing in these properties does so with a perception of blood on their hands.

- Organized crime: They often back illegal miners or use them to launder their illicit proceeds, and can influence local and regional police and politicians. In parts of Central America, drug smuggling routes northward to the U.S. have been threatened by the awarding of mining claims, leading to robust opposition to mining.

- Farmers: They oppose mining particularly when they rely on irrigated local water supplies and fear that their livelihood will be threatened by water depletion or contamination that results from mining activity. Collective farmers in Guatemala and farmers in Colombia have been vocal opponents of mining.

- Indigenous leaders: 15 of the 21 nation signatories of the ILO 169 Convention on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples rights are located in the Americas, which explains the scrutiny over the issue and resulting reputational risks for miners. The question of indigenous rights is a global media favorite. When President Temer tried to open new regions for mining exploration in the Brazilian states of Para and Amapa, NGOs reached out to celebrities, who were more than happy to ride an indigenous cause that would benefit their own image.

- Unscrupulous journalists: Underpaid and poorly trained, journalists in Latin America often sell their media access to the highest bidder, either writing fluff for corporate clients and their PR agencies or working against investors, either to extort money or operating in the interests of investment opponents.

CSR Isn’t Remotely Enough

For many years, miners brought a playbook of a few CSR strategies to each project, dedicated a finite budget to CSR and let the program operate autonomously and in isolation. They were the do-gooders that helped slap a coat of paint on what is a necessarily dirty business. CSR was kept out of the C-suite and any serious decision-making. If such an approach was flawed in the past, it is downright reckless today. Local communities have far more power than ever before and are much more sophisticated and ambitious in how they exercise that power than they did in the past. Connectivity allows local communities to inform themselves, understand what other communities have negotiated and seek advice from willing NGOs and other natural opponents of mining. There is a rash of local community referenda across Colombia, Guatemala, Argentina, Peru and elsewhere that have halted, cancelled or currently threaten more than 50 mining projects in Latin America.

Miners require a more sophisticated approach to managing their reputation, beginning with investing in robust surveying and intelligence gathering.

Best Practice: Investing in Information Gathering

Before investing in a property, the due diligence assessment of an asset should include a reputational audit of mining in the area—and of the buyer’s name. Surveys of the local community should be conducted to gauge their opinion of mining, quantifying both their fears and aspirations related to mining. An understanding of the local power players, their motives and to whom they are answerable is also crucial. The cost in time and money to respectively win the hearts and minds and understand the motivations of the local community and its stakeholders must be woven into the valuation process.

Before visible signs of investment in a mine take place, community outreach should begin by listening, which includes regularly surveying the community (and national public) and establishing roundtables to hear the concerns—and yes, demands—of local stakeholders. The same roundtables eventually become a platform through which the miner can convince the most influential people in local communities of the merits of their proposed approach to mining.

Beyond the public listening posts established, it is important to monitor discreetly any dubious alliances and stakeholders whose interests inherently clash with the mine to initially understand their motives and then mitigate the actions those motives provoke. Links back to greedy litigators in the capital city or opposition parties looking to stain the reputation of the government by association with the mine are the sorts of dynamic that only discreet investigation can uncover. But such monitoring takes time to mount and should be therefore undertaken on a light but constant basis, ready to be ramped up or focused on a single issue when needed.

Knowing the facts, conducting one’s own analysis (via respected third parties) of soil and water impact and other crucial environmental data is essential to counteract the actions of unscrupulous journalists acting in cahoots with opponents of the mine. Even professional journalists are vulnerable to manipulative forces. With declining investigative budgets, journalists of all stripes increasingly rely on social media and other malleable sources to build their reportage. Miners should invite scrupulous journalists to the mine to show them directly how things operate.

For years, a lack of information flow in Latin America induced miners to operate semi-secretly with their plans and tactics, keeping everyone but a handful in the national government under-informed. But now we live in a hyper-information age, where even a humble local resident can access limitless information about a mining company, a site’s history, the dangers of mining and the level of royalties and other taxes paid around the world. Managing reputations in the internet age requires both greater miner transparency, especially with the local community, and a more robust information collection approach, to satisfy stakeholders, proactively fend off unscrupulous actors and counter misinformation.

Explore More

Over the past 10 years we’ve completed nearly 200 projects for mining companies, with a specialized focus in risk management that includes helping miners manage opposition, political interference, regulatory instability, security risks and much more.

Contact us to learn more about how we can apply our deep LatAm mining jurisdiction knowledge to handle the risks your company is facing.

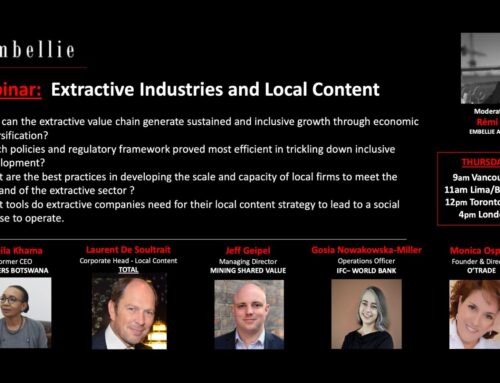

Dr. Remi Piet is a Director at Americas Market Intelligence (AMI) and co-leader of the firm’s Natural Resources and Infrastructure Practice. Remi leads political and other risk analysis activities for the mining, energy and infrastructure sectors in Latin America. He has worked on projects in more than 60 countries across Latin America, Asia and Europe and taught at several universities including the University of Miami, HEC (Paris) and Qatar University. Be it a snapshot country and counterparty risk analysis ahead of an asset purchase or the on-going monitoring of on-the-ground risks for miners and energy players, Remi leads the design and execution of bespoke engagements for our clients.